INSTITUTIONAL SPOTLIGHT: THE MIRABAL SISTERS HOUSE MUSEUM

The Women Against Trujillo’s Dictatorship: The Mirabal Sisters House Museum

By Marlin Ramos

From 1930 to 1961, thousands were killed, tortured, or imprisoned under the tyranny of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina’s dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. The Mirabal Sisters House Museum (Casa Museo Hermanas Mirabal) is an immersive experience that teleports you back to this time period as it introduces you to the intimate lives of three revolutionary sisters who led a clandestine movement against the dictatorship. Patria (1924–1960), Minerva (1927–1960) and María Teresa (1935–1960) are the three Mirabal sisters renowned for their activism and sacrifice.

The Mirabal sisters grew up aware of Trujillo’s tyranny from a young age. While in boarding school, Minerva met a classmate whose family members were killed by Trujillo’s orders. This led Minerva to converse with her sisters about the political injustices present in her country and to seek out other voices of opposition.

In 1949, the Mirabal family was invited to a party organized by Trujillo. Aware of the danger that could arise from declining the invitation, the family was forced to attend. That night, Minerva danced with Trujillo several times and rejected his inappropriate advances. At one point Minerva also left him in the middle of the dance floor and the family left the party early shortly thereafter. The act of leaving any event before Trujillo was considered disrespectful to the dictator. As a result, the next day Minerva and her parents were imprisoned, and their family property confiscated. After several weeks, Minerva and her mother were allowed to return to their home in Ojo de Agua where Minerva was held in house arrest, but her father remained detained longer in Santo Domingo.

In 1957, Minerva graduated with honors from law school, becoming one of the first women in the country to receive a law degree. However, she was denied state authorization to practice likely because of her opposition to the dictatorship.

In 1959, the Mirabal sisters, Minerva’s husband Manuel Aurelio “Manolo” Tavárez Justo, and many others founded the revolutionary movement Movimiento 14 de Junio (June 14th Movement), known as 1J4. The sisters were called “Las Mariposas” (the butterflies) as a covert way of referring to their work within and outside the organization. Las Mariposas began to lead an organizing movement among the middle class, holding and attending secret meetings and distributing pamphlets detailing Trujillo’s violations.

In January 1960, 1J4 representatives from all over the country were summoned to plan the structure of the movement and prepare for an uprising. However, word about their operations had reached Trujillo. Soon Minerva, María Teresa, their husbands, and other participants were imprisoned. Under pressure from the United States and the Catholic Church, which had begun criticizing Trujillo’s regime, the dictator eventually released the two sisters but not their husbands. Once freed, Las Mariposas continued to threaten the stability of the dictator’s regime and his ego. On November 25, 1960, as the three sisters were driving back from visiting Minerva and María Teresa imprisoned husbands, they were stopped by Trujillo’s henchmen and beaten to death. Trujillo’s henchmen pushed the car off a cliff to make it appear as an accident.

Much of the public remained skeptical about the sisters’ “accidental” deaths and the international community also expressed its disdain for their deaths. In May 1961, Trujillo was assassinated, and his 31-year tyranny finally came to an end. The deaths and activism of the Mirabal sisters were not in vain; they are credited as the main factors that garnered international pressure to help end the regime and motivated many Dominicans to act courageously against the dictatorship.

Inside the Mirabal Sisters House Museum. Clockwise from top left: formal dining room, casual dining room, central living room, María Teresa’s room. Image credits: Marlin Ramos.

The Mirabal sisters’ house was originally the home of their mother, Mercedes “Chea” Reyes Camilo. The sisters spent the last ten months of their lives in this house, moving in after Minerva, María Teresa, and their husbands were imprisoned for their opposition to the dictatorship and their own homes were destroyed. Surveillance of their mother’s house and harassment of the family continued until the day they were brutally beaten to death.

Even before it became a museum, the house attracted a large visiting public. After the death of the sisters’ mother, the surviving sister, Bélgica “Dedé” Mirabal (1925–2014) decided to open the house permanently to the public and turn it into a museum. In 1994, Dedé established the Mirabal Sisters Foundation, which has since governed the museum.

The house was built in 1954 and remains in the same condition as when the sisters lived there, with the exception of the necessary conservation carried out on the floors, ceiling, and kitchen pantry. Dedé Mirabal, as president of the Mirabal Sisters Foundation, directed it until her death in 2014. Subsequently, the Foundation was directed by Noris González Mirabal, Patria’s daughter, and is currently presided over by Manolo Tavárez Mirabal, Minerva’s son. The museum is guarded by the military police because part of it is an extension of the National Pantheon.

Here are five impactful artifacts on view at the Mirabal Sisters House Museum that tell the sisters’ story.

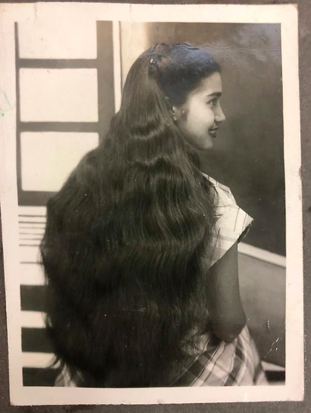

María Teresa’s braid

María Teresa Mirabal was known for her long dark brown hair, which she often wore braided. After María Teresa was assassinated, her sister Dedé cut off her braid as a memento. The braid is displayed in María Teresa’s room in a closed case among her other belongings. Originally, the braid occupied the entire length of the box, but it has shrunk over time due to the natural decaying process. María Teresa’s braid helps us understand how the Mirabal family began to mourn the three sisters.

1J4 Movement flag

Minerva Mirabal was an artist and the most active revolutionary of the sisters. In her room hangs the first flag made for the 1J4 group. The black at the bottom symbolizes mourning for the lives lost during the dictatorship. The green at the top symbolizes hope that the country would be free from the tyranny of the dictatorship and human rights would one day be restored. The group’s name pays tribute to the day an expedition of 198 armed men, who had been training in Cuba, led an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the dictatorship on June 14 and 20, 1959. The 1J4 group was founded that same year and Manuel Aurelio “Manolo” Tavárez Justo, Minerva’s husband, was elected its president, although others present had also proposed electing Minerva.

Minerva designed and sewed the flag herself using the sewing machine that is displayed in her room. The flag reminds us of Minerva’s artistic talent and the many different ways she contributed to the 1J4 movement.

Belongings from the day they were assassinated

On display are also the purses of the three sisters and the contents found within them from the day they were pulled over and violently murdered. Among these belongings are a prayer card with a mother and child, pages torn from a book (perhaps the Bible) featuring St. Peter Nolasco, a handwritten prayer card entitled “Peace Christ Peace – Peace Christ Peace,” a memo from the funeral of their father Enrique Mirabal Fernández, a hair roller, small scissors, and several other items. In a separate case, next to the purse display, a kitchen towel that was used to wipe the blood from the sisters’ faces is preserved. These powerful objects teleport museum visitors to the scene of the crime and allow us to witness the tragic event of their murders.

Sculptures made by Minerva during her imprisonment

Upon entering the museum, on the right, there is a display case with several sculptures made by Minerva while she was incarcerated in the infamous La Victoria prison in 1960 for her participation in the 1J4 movement. Although it was forbidden, the family paid the prison guards to give Minerva sculpting materials that she had requested.

In the display case is an unfinished sculpture of the face of Minerva’s daughter, Minou Tavárez Mirabal. On one side of the bust is a photo of Minou that shows us the sculpture’s similarity, although Minerva did not have a photo when making the sculpture and used her memory as a reference. The other sculpture in the display case is a three-leaf clover carved from a piece of stone taken from the wall of the prison and given to Doña Chea by some of the prison’s survivors, symbolizing love and faith as well as family. There are several other sculptures and objects in the display made by Minerva during her imprisonment. The sculptures she made demonstrate how vital artistry was to her identity—so much so that she spent part of her time in jail creating.

Sisters’ Tombs

In 2000, the remains of heroines Patria, María Teresa, Minerva, and national hero Manuel “Manolo” were moved from their original resting places and buried in a purpose-built mausoleum in the garden that surrounds the museum. The four heroes are buried in tombs placed in the ground perpendicularly to a central fountain that has a continuous flow of water to symbolize eternal life. Each tomb is covered with a piece of stone typical of the region. At the time of the transfer of their remains, Hipólito Mejía, President of the Dominican Republic at the time, issued a decree declaring the garden and the mausoleum an extension of the National Pantheon, based in Santo Domingo, the country’s capital. The House Museum and garden are revered as a sacred place considering that it also serves as a cemetery for these four heroes of the Dominican Republic.

Legacy Today

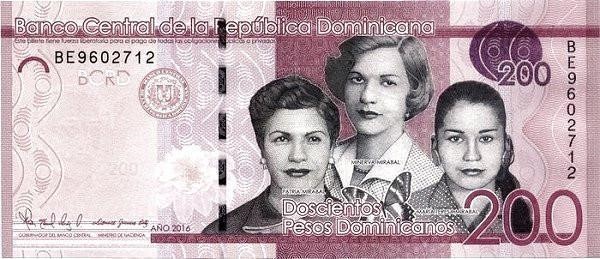

The Mirabal sisters are international historical figures. In 1999, the United Nations declared November 25, the anniversary of the day the three sisters were brutally murdered, as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The novel In the Time of The Butterflies, written by Julia Alvarez and based on the sisters’ story, was a finalist for the United States’ National Critics Book Award in 1994. Numerous other artists have paid tribute to them internationally in paintings, films, literature, and murals. The faces of the three sisters are printed on the 200 Pesos Dominican bill. In 2007, to further commemorate their legacy, the National Congress changed the name of the province where the sisters were born and where the House Museum is located from “Provincia Salcedo”to “Provincia Hermanas Mirabal”(Mirabal Sisters Province). Throughout the country and especially in the province, butterflies (the sisters’ code name) are a common icon on business storefronts and in neighbourhood parks to remind city dwellers of the political genesis that these sisters inspired.

Special thanks to the Mirabal Sisters Foundation for allowing us to photograph in the museum and the museum’s administration for their immense support with this article.

Sources

Casa Museo Hermanas Mirabal. “Guion Recorrido Museo Hermanas Mirabal” (Mirabal Sisters Museum Tour Script), provided by the museum’s administration.

Blackmore, Lisa. “Violence in the Jardín de (la) Patria: The Monumentalisation of the Mirabal Sisters and the Trauma Site in the Dominican Postdictatorship / Violència al Jardí de (la) Pàtria: La monumentalització de les Germanes Mirabal i el lloc de trauma en la postdictadura dominicana / Violencia en el Jardín de (la) Patria: la monumentalización de las hermanas Mirabal y el sitio de trauma en la posdictadura dominicana.” Mitologías Hoy 12 (2015): 101–17. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/mitologias.277.

Edwards, Gavin. “Overlooked No More: Dedé Mirabal, Who Carried the Torch of Her Slain Sisters.” New York Times, January 13, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/obituaries/dede-mirabal-overlooked.html.

Ramos, Marlin. Notes from a guided tour of the museum. February 19, 2022.

Robinson, Nancy. “Women’s Political Participation in the Dominican Republic: The Case of the Mirabal Sisters.” Caribbean Quarterly 52, no. 2/3 (2006): 172–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40654568.

Pruitt, Sarah. “How the Mirabal Sisters Helped Topple a Dictator.” History.com, March 8, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/mirabal-sisters-trujillo-dictator.